Introduction

In an age where morality can be tested at the click of a button, the worlds of ancient philosophy and modern gaming unexpectedly converge. Video games, once regarded as simple entertainment, have evolved into interactive experiences that question ethics, consequence, and free will. Intriguingly, these themes mirror the timeless teachings of the Bhagavad Gita, particularly its philosophy of karma and dharma, the eternal interplay between action and duty.

Arianna Raru’s essay, “Karma, Choice, and Consequence: The Bhagavad Gita’s Moral Philosophy in Video Games,” brilliantly bridges these two worlds, illustrating how Arjuna’s moral struggle on the battlefield of Kurukshetra finds new life in virtual landscapes, from Fallout to Life is Strange. The dialogue between Krishna and Arjuna becomes, in a sense, the precursor to the moral decision-making players face in today’s games, proving that even in digital realms, the question of “what is right?” never loses its relevance.

Karma and Dharma: The Core of Action

At the heart of the Bhagavad Gita lies the concept of karma, the moral law that governs action and consequence. In Krishna’s teachings to Arjuna, karma is not merely about physical acts but about intention and detachment from results. As Krishna advises:

“Thy right is to work only, but never with its fruits; let not the fruits of actions be thy motive, nor let thy attachment be to inaction.” (Bhagavad Gita, 2:47)

Here, action (karma) and duty (dharma) are inseparable: one cannot exist without the other. Dharma represents one’s righteous path or divine obligation, while karma embodies the sum of one’s every deed, thought, and choice. The essay highlights this interdependence beautifully: “Dharma without karma is lame, and karma without dharma is blind.”

Arjuna’s conflict in the Gita encapsulates this tension. He knows that killing is wrong, yet refusing to fight would mean abandoning his divine duty as a warrior. Krishna’s counsel reframes morality itself: right action is not about avoiding harm or seeking reward but performing one’s duty selflessly, without attachment to outcomes.

This philosophical stance forms the foundation of Karma Yoga, the path of selfless action. It asks us not to pursue virtue for personal gain but to act in alignment with our purpose. This is a lesson that, as A. Raru shows, reappears in the moral mechanics of modern video games.

From Sacred Text to Popular Culture

In the contemporary West, the meaning of karma has been diluted, often reduced to the catchy adage “what goes around comes around.” Raru critiques this simplification as a distortion of its original metaphysical depth.

Pop culture frequently treats karma as a short-term feedback loop, equating it with cosmic payback rather than the spiritual law of ethical causation. In this modernised form, karma becomes transactional: good deeds yield rewards, bad ones bring punishment. A notion epitomised in pop media, from social-media memes to Taylor Swift’s hit song “Karma”.

Yet this oversimplification paves the way for an interesting experiment in storytelling: video games. As the cited essay observes, gaming is uniquely suited to exploring karma, since its very structure revolves around action and consequence. Every player decision has the potential to reshape the game world, making the philosophy of karma, the relationship between deed and destiny, both playable and personal.

Moral Mechanics: The Rise of Karma Systems in Gaming

From the pixelated arcades of the 1980s to today’s sprawling open worlds, video games have evolved into moral laboratories. The essay notes that while early games equated consequence with winning or losing, the concept of “actions have consequences” has since matured into complex systems of morality, reputation, and narrative branching.

A prime example lies in Fallout 3 and Fallout: New Vegas, both of which implement explicit karma systems. Players earn or lose “karma points” based on their choices (stealing, killing, helping others, or showing mercy). These points then shape how NPCs and communities respond. As Raru writes, “the morality system is so intertwined with community reputation that ethics shift depending on factional perspectives.”

In one memorable quest, “The Power of the Atom,” players must decide whether to detonate or disarm a nuclear bomb at the centre of a small town. Detonation brings wealth and infamy; disarmament brings respect and belonging. This mirrors Arjuna’s moral dilemma: the struggle between personal gain and cosmic duty, between desire and righteousness.

The essay also critiques such systems for their binary simplicity. In many games, morality is presented as a black-and-white spectrum, with “good” and “evil” choices clearly labelled. This design removes ambiguity, denying players the reflective space to question their motives, just as Arjuna initially sought to escape his duty rather than confront it. As Raru cites from Melenson’s The Axis of Good and Evil, “The moral axis cannot assess a player’s intentions. Any action that yields a bad result awards evil points, regardless of the player’s goals or motivations.”

Yet even in their flaws, these systems invite introspection. They ask players to consider not just what they do, but why they do it: a notion deeply aligned with the Gita’s call for self-examination in action.

Choice, Freedom, and the Illusion of Control

As moral decision-making became a gaming staple, developers began creating “choices-matter” games: experiences where every decision supposedly alters the story’s course. But as the essay insightfully notes, this promise often rings hollow. Many such games offer only the illusion of choice, guiding players toward predetermined outcomes disguised as freedom.

Scholar Antranig Arek Sarian’s analysis, sheds light on this paradox. Quoting media theorist Lev Manovich, he writes:

“By following a pre-planned path, the user is expected to inhabit the mind of the designer and mistake it for their own.”

This has the effect of transforming moral choice into a mirror of Arjuna’s spiritual test. Like Arjuna, the player faces a series of “choices” that ultimately reaffirm a pre-ordained cosmic design. Some games discipline the player through didactic structures, offering one correct path, while others, called exploratory games, allow players to wander freely among outcomes. The most philosophically rich experiences, however, are what Sarian calls “reflective games”: titles that blur right and wrong, forcing players to question their motives and, in doing so, themselves.

Life Is Strange: The Weight of Every Choice

In Life Is Strange, the philosophy of karma becomes profoundly human. The essay’s analysis of this game captures its emotional and ethical complexity: a story where each decision feels small yet ripples through time, echoing the butterfly effect.

The protagonist, Max Caulfield, discovers she can rewind time and alter events, including saving her best friend, Chloe, from death. Yet every time Max uses her power, reality shifts, causing new tragedies. Each action creates unintended consequences, forcing the player to question whether “doing good” is truly possible.

As Raru notes, the game reminds players that “their actions will have consequences”, visually symbolised by a butterfly, a reference to chaos theory’s delicate interconnection of events. Like Arjuna, Max must grapple with the burden of moral responsibility: no matter her intention, every intervention changes destiny’s balance.

By the finale, players must choose between two devastating options:

- Let Chloe die and preserve the natural timeline, or

- Save Chloe and allow the city to be destroyed.

It is a choice between personal love and universal order, mirroring Arjuna’s realisation that true virtue lies in detachment from desire. Both Max and Arjuna confront a truth the Gita articulates with precision: the only way to transcend moral paralysis is to act according to dharma, not emotion.

Life Is Strange thus transforms Krishna’s lesson into interactive form. It shows that even when we possess the power to change fate, the most ethical act may be acceptance, letting life unfold as it must.

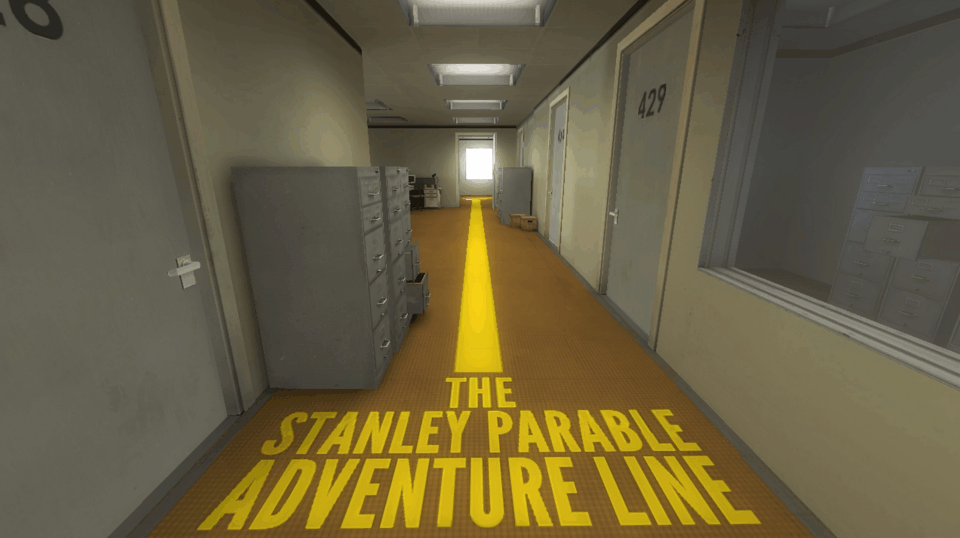

The Stanley Parable: The Paradox of Freedom

If Life Is Strange explores consequence, The Stanley Parable examines agency itself. As the essay notes, this game dismantles the illusion of free choice in video games, and by extension, in life.

The player controls Stanley, an office worker who discovers his colleagues have vanished. A witty, omnipresent Narrator describes Stanley’s every move in the past tense, as though his actions have already been determined. The first major decision comes almost immediately:

“When Stanley came to a set of two open doors, he entered the door on his left.”

The player may follow the instruction, or defy it by entering the right door. Each choice leads to a new branch of the story, creating a web of endings that seem to promise autonomy. Yet, as the author highlights, the paradox becomes clear: even rebellion is part of the plan.

The “Freedom Ending” rewards obedience, while the “Not Stanley” and “Museum” endings mock the player’s illusion of control. In one scene, a voice commands, “Stop now and it’ll be your only true choice. But whatever you do, choose it! Don’t let time choose for you.”

This existential twist mirrors the Bhagavad Gita’s view of destiny. Krishna tells Arjuna that his path is already written, his actions are but instruments of divine order. Likewise, The Stanley Parable reveals that even when we believe we’re choosing freely, our possibilities have already been mapped by design.

As A. Raru observes, “No matter what men try to do, what choices they think they’re making, their path has already been decided by the cosmos.” Both Krishna’s universe and The Stanley Parable’s digital world reduce human agency to interpretation, suggesting that liberation lies not in defiance, but in awareness.

The game’s haunting message –“The end is never the end” – resonates deeply with the Gita’s concept of Samsara, the cycle of rebirth. Only by accepting the divine script, and performing one’s duty within it, can one transcend the loop.

Persona: The True Karma System

After examining moral binaries and illusionary freedoms, the author ends her analysis with the Persona series, a rare example of karma represented authentically. Unlike games that track morality through points, Persona translates karma into daily action and self-cultivation.

Each day, the player chooses how to live: study, socialise, work, or rest. Every action shapes the protagonist’s relationships, skills, and ultimately, fate. The player’s gameplay is built brick by brick, by the series of actions they choose to undertake.

This cumulative design perfectly echoes the Gita’s principle that every act contributes to spiritual progress. In Persona, success depends on leading a balanced life, fulfilling one’s duties in friendship, study, and courage. Failure to do so means repeating the cycle, much like reincarnation, until harmony is achieved.

In this way, Persona transforms karma from an abstract moral scale into a lived experience of discipline and growth. The lesson is unmistakable: enlightenment, like victory in the game, is earned through mindful action over time.

The Persona games embody Karma Yoga in playable form. They remind players that the smallest, most mundane decisions, how we spend our time, how we treat others, carry weight in shaping destiny.

Choice, Duty, and Digital Dharma

Across these examples – from Fallout’s binary morality to The Stanley Parable’s paradox and Persona’s spiritual realism – a clear thread emerges: the philosophical depth of the Bhagavad Gita continues to illuminate modern narratives about choice and consequence.

The essay frames Arjuna as a prototype for the modern player. Like him, gamers must navigate a world where moral clarity is rarely guaranteed, where outcomes are uncertain, and where duty often conflicts with desire.

The Gita teaches that liberation (moksha) comes not from avoiding choices, but from performing them without attachment. This echoes through gaming experiences where true freedom is found not in the illusion of control, but in understanding the framework that defines it.

Both the ancient scripture and the modern game console challenge us to confront the same question: what does it mean to act rightly when every action carries consequence?

Conclusion: The Eternal Game of Karma

The dialogue between Krishna and Arjuna endures because it captures something timeless: the tension between free will and destiny, between choice and duty. In today’s digital worlds, players unknowingly rehearse this very dialogue every time they press “continue.”

As Raru’s essay eloquently concludes, “The Bhagavad Gita explains that a person’s trajectory must be followed in order to reach moksha, the same way Stanley-the-avatar needs to listen to the Narrator’s orders if he wishes to exit the prison-office.”

Whether in scripture or simulation, the lesson remains: our actions define us, but liberation lies in detachment from their fruits. Video games may not promise enlightenment, but they invite players, much like Arjuna, to reflect on the ethics of their choices, the purpose of their actions, and the consequences that follow.

Perhaps the truest victory, both in life and in play, is not winning at all, but understanding the rules of the cosmic game.

Source:

Arianna Raru, “Karma, Choice, and Consequence: The Bhagavad Gita’s Moral Philosophy in

Video Games